‘My work is purely autobiographical. It is about myself and my surroundings. It is an attempt at a record. I work from people that interest me and that I care about, in rooms that I live in and know.’

This Valentines Day, LG thought it would be appropriate to pay homage to a much loved artist, and one of the greatest figurative painters to date, Lucian Freud. Lucian Freud Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery is the last exhibition the artist enthusiastically agreed to be involved in before he died in July last year.

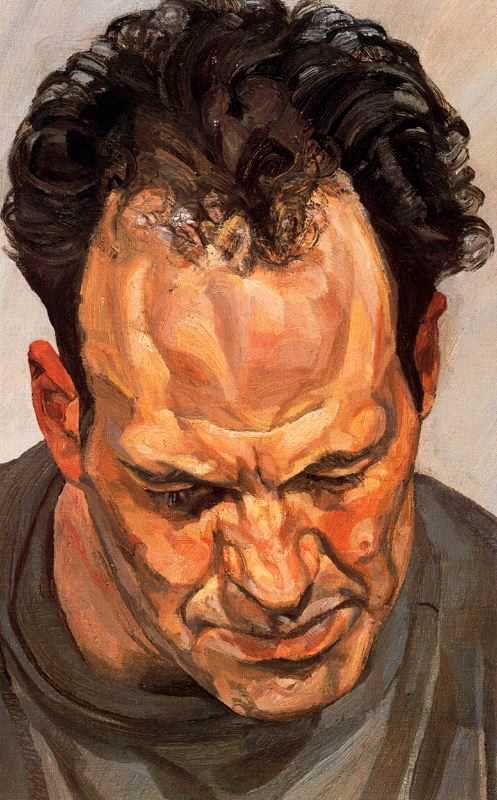

Freud has an affiliation with flesh that very few artists have come close to achieving through paint; the artist understands every membrane before applying his brush to the canvas. Sitters of the artist have commented on how lengthy the sessions for portraits would be: often there was time for conversation and singing and reciting poetry, but all the while Freud would gaze piercingly at his subject, taking in their every breath, twitch and flicker of movement to memorise for his work.

This was not usually a comfortable gaze to be trapped within, indeed Freud confessed himself that he was ‘visually aggressive’ in his staring. However, thank God he did when the result is such subtlety in palette and draftsmanship. Through Freud we see membranes, fluids, jellies and hair –sometimes literally through three-dimensional swellings on the canvas, achieved by Freud’s characteristically thick impasto.

It is notable how strongly Freud’s early work deviates from this spirit; his work from the 1940s for example is both resolutely flat and eerily surrealist in comparison, all the fleshy dynamism completely absent. While the majority of contemporary artists were set on first mutilating, and then discarding the human body in favour of abstraction, Freud treated it initially like the Holy Grail. As Michael Auping observes, ‘Abstraction was not a consideration for Freud’, his work is about bringing to life, pushing the viewer into an awkward position of realism and bringing flesh to the senses, until we can practically see the blood pumping around the bodies on the canvas.

Leigh Bowery, (Seated) 1990

Man with a Feather, (Self-portrait) 1943

We loved the use of colour in the skin tones in Flora with Blue Toenails, 2001 varying from grey-green murky strokes across the torso to taut stretches of purple and vermillion (even brighter in the actual painting) in the thighs and down to the feet, as though the lower half of the body was red raw, flayed even. Great ominous shadow creeping into the forefront too.

Flora with Blue Toenails, 2001

I was also struck in particular by the tender portraits the artist painted of his mother towards the latter part of his career. In many of these paintings, Freud takes particular care over the subtle marks and textures found in the fabrics of her clothes, the soft wools of cardigans and delicately patterned paisley nightclothes, which are in turn complemented by the heavily lined yet quietly serene face.

The Painter’s Mother Reading, 1975

Thank you Lucian Freud, for the many reasons you’ve given us all to love painting.